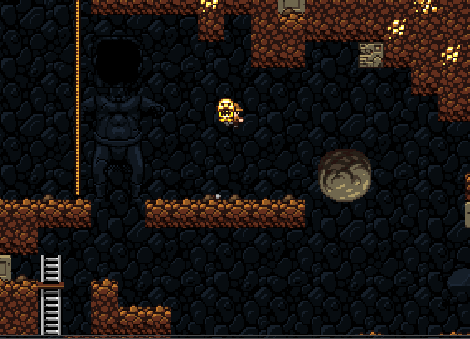

You’re 2 levels down a cave that could kill you in an instant, and you see a shiny golden object in the middle of a clear area. You stop, wary: Item or Enemy? Fight or Flight?

Your game-trained cortex ticks off “Item” and “Trap?” and selects “Pick up” from the vast table of responses you’ve honed over the years. When you drop down and grab the idol the room starts rumbling. “Trap?” and “Boss?”, “Bad” and “RUN” shouts your cortex, and you flee. The boulder that drops from the ceiling and rolls towards you with lethal force seems both surprising and inevitable. Of course a boulder was going to roll out when you grabbed the idol, you mutter to your crushed spelunker. What else could have happened?

It’s shamefully rare for games to confront you with a mystery and force you to figure out how to handle it, but Spelunky does this constantly. It teaches you the basic mechanics, then unleashes you on an environment full of things that act according to rules you haven’t been told. Everything new you meet provokes three stages, in order. The sudden stop and careful assessment: “What is this going to do? How should I approach this?” The careful poke: “Let’s see what happens if I…” And the discovery: “Oh! Ahahaha!”

What stops it from being frustrating trial and error is that each object is carefully covered in a varnish of tropes. A woman in a red dress, yelling “Help!”; a black altar; a pistol, a compass, and a shotgun, with an old man standing behind them. Clues. These things tap into our deepest ingrained cultural brain-bits, making our cortex scream exasperated instructions over our shoulders. A damsel – maybe I should rescue her. Ah, a shop- I should buy things here. A bloodstained altar? What happens if I put the Damsel on – oh! Ahahaha!

The Binding of Isaac fails at this by making the clues too obscure, the responses too obvious. Picking up a tube of lipstick makes your range go up – but you won’t question it, because you know to just instinctively pick up any items you find. One series of items looks nearly identical, with random effects when consumed – no need to assess, just eat it and see if it the outcome was good. The assessment and careful poking is replaced with blind stabs in the dark.

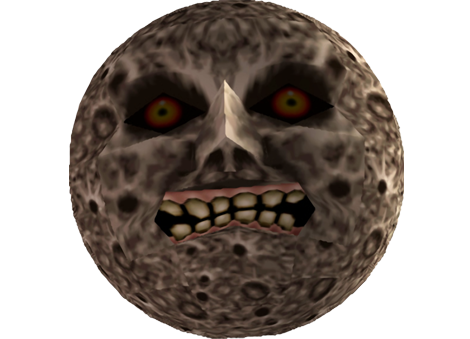

Spelunky builds itself entirely on these unspoken rules, making itself into an experience of constant experimentation and discovery. Other games- Super Mario Brothers, Majora’s Mask – put their mystery mechanics into side-quests instead, leaving the main quest clear and blatant and the unspoken rules providing mystery around the edges. Both work well, but the latter is easier on newbies; The hardcore players can tangle with the mysteries of the world, while the majority just go about their business in a world full of the strange unknown.

Filling the world with things the player doesn’t understand makes the game seem limitless, full of wonder. Every time the player finds the answer to some unexplained conundrum, they’re filled with a sense of spontaneous joy. The horizon expands. The world peels back. Every rock and item seems like it could hold the answer to an incredible mystery.

And that’s what we’re all trying to do here, right?